Today’s episode of Save Vs. Rant is all about novel ways of telling classic stories, be they real-world legends, existing fiction, outdated modules or other sources of inspiration.

Something that we touched on in this episode is how every monster has a connection to stories – modern or classic – from which to draw inspiration. I’d like to talk a little bit more about that.

Consider, the common orc, a mainstay of fantasy games. The orc originated in Lord of the Rings, where they were fearsome warped creatures created by Sauron to form an army. They are dull-witted, violent, savage and, most importantly, die pointlessly for expressly evil causes. In short, they are a perfectly unambiguous enemy. As a whole, they are a perpetual aggressor in the world. In D&D’s interpretation, they are religiously devoted to a god of slaughter with a special hatred to elves, and in Pathfinder they are creatures of the literal underworld come to conquer everything with nihilistic glee.

Goblins, as they are understood in a gaming sense, are kind of an amalgam of mythological goblins (typically small mischievous sprite creatures) and Tolkien’s goblins (just an implicitly diminutive way of saying “orc”). D&D in all its incarnations have taken it to mean “Tolkien’s goblin” while Pathfinder veered more towards “fairly tale goblin, but without inherent magic.” Changeling: the Lost makes goblins a sort of lesser fae creature.

All of these are valid interpretations of the materials, but it should be noted that there is a broad spectrum of things that can be called “goblin” without the term being nonsensical. One could conceive of settings where “goblin” could be anything: literal little green space aliens! Fairy creatures! A term for all supernatural creatures! The fun size version of Tolkien’s orcs! Pathfinder’s miniature misshapen mischievous monsters! All “feel” like something that could be a goblin. Perhaps “goblin” being an alternate term for a hag, or a kind of shaman might be awkward, but “goblin” is remarkably flexible with lore!

Less so with “orc:” it would be strange to imagine orcs as being very smart or very beautiful. The term “orc,” in all its incarnations, have been associated with ferocity and bloodlust. Shadowrun’s orcs still feel like orcs because, despite being well out of a fantasy settings, they are something we are comfortable calling orcs. Pathfinder, D&D and most other fantasy orcs are largely interchangeable, with only a few version exhibiting notable differences to culture and organization. Generally speaking, though, orcs may be cunning, bold or honorable (as in the World of Warcraft and some of the classic D&D settings) they are always boorish and savage.

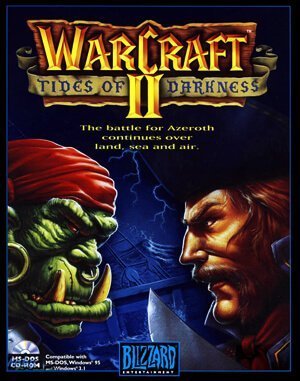

We don’t have to have savage orcs, but we must have it continue to resemble an orc, or calling it an orc becomes nonsensical. Look at the box art for Warcraft 2: Tides of Darkness:

That orc is a classic Treasure Island version of a pirate, and it feels just as much an orc as when it was wielding a battle axe! How could we expand on this? Maybe they have control of or ties to some violent sea creature such as sharks or even dolphins . Maybe they are fond of particularly brutish weapons such as cannons that fire burning slag or vicious boarding maneuvers. It’s not hard to picture orcs as wild west outlaws wielding a pair of shotguns, wretched primitive survivalists with savage traditions, bloodthirsty shamans of lost gods or soulless servants of dead lords. An orc that was a beautiful, graceful willow-like elf is a stretch because it embodies none of what it traditionally means to be an orc. Playing to established stories makes a connection seem real.

Moreover, one does not need to know the lore of the Wisconsin Hodag to enjoy including it in a campaign incidentally, but if this Hodag (so specific a creature) doesn’t resemble this creature in any way, it seems a shame to bother to borrow the name.

An important question to ask yourself when you choose to go with something unique rather than sticking to the establishment: am I only doing this because it makes my setting unique? Does it serve the needs of the setting in a deeper way? As an example, there are no orcs in Dragonlance. This was a deliberate decision. The “cannon fodder of impending doom” role of the setting was taken by the draconians who, like orcs, represent little threat in small numbers, but an existential threat to good society en masse. The sudden emergence of these creatures is eventually a crucial plot point, and proof that evil has broken its word and violated a terrible taboo. While draconians are still uniquely Dragonlance (although 4th edition introduced them in a general monster manual), they are not unique solely to be unique.

While it is easy to run the risk of becoming an “everything but the kitchen sink” setting by including too many fantasy tropes, Dragonlance, likewise, serves as an example of including more than one incarnation of something, with five different types of elves, two of which embody the two common fantasy interpretations of elves: the wild forest elves and urbane high elves. D&D 4th edition accomplished much the same sense of separation between the two interpretations with the Eladrin taking the role of high elves, and “Elves” referring to nature-connected elves.

I know I’ve mentioned Dragonlance a few times now, but I think it’s contains really good examples of how to do a fantasy archetype. It has wizards dedicated to good, evil and balance. It was one of the codifiers of the “metal dragons good, chromatic dragons evil” system employed in D&D ever since. It has a unique interpretation of halflings, a very traditional interpretation of dwarves and a now-classic interpretation of gnomes (which still felt like something that would be called a gnome). It is one of the first settings I really appreciated for diverging from standard fantasy fare without feeling forced.

The point is never to stifle uniqueness. It’s to ensure that uniqueness is not forced or alien, but emerges from familiar ideas. As much as we crave uniqueness, it can often be just as powerful to reimagine the familiar and try to see it from a new perspective.

Unless we’re talking about killing Batman’s parent’s for the millionth time. Or rebooting Spider Man again. Or making yet another zombie movie. You gotta’ know when things are played out.